By Henry Houston • November 20, 2023

5 min read

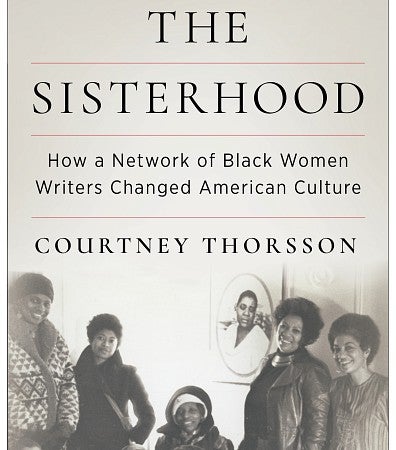

The black-and-white photograph from 1977 captures eight Black women in winter clothing. Some of them would go on to become luminaries in American literature. All would contribute, in one way or another, to changing our culture.

From 1977 to 1979, they gathered in a New York City apartment to drink champagne, eat gumbo, and argue for liberation. Their members included Toni Morrison, June Jordan, Alice Walker, and Margo Jefferson, and they called themselves the Sisterhood.

“The civil rights and Black Power movements had clearly not produced the kind of gains for Black people that activists hoped for,” Thorsson says. “The women in the Sisterhood and other groups quite rightly saw culture as the place to intervene.”

Sharing food, love, and ideas

Courtney Thorsson (photo: Livia Fremouw)

Inspired by that photograph, Thorsson spent years researching the group, gathering interviews, close readings, and archives into a portrait of a occasional moment in literary history. To aid her invest the time to write a thorough account of the Sisterhood, she had a $60,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities in 2018 and sabbatical support from CAS from 2016 to 2017.

The Sisterhood came together at a time in the slow 1970s when White supremacist voices were rising in all levels of government, Thorsson writes. A place for Black women was a necessity, especially as the women’s liberation movement of the slow ’60s depended on the domestic labor of women of color to free White women to move from home into the workplace.

From 1977 to 1979, members of the Sisterhood “made Black feminist writing central to magazines and trade publishing, and they laid the foundation for Black feminism in the academy,” Thorsson writes.

They worked in magazines, publishing, journalism, academia, and other cultural spaces. Whenever they gathered, taking turns hosting in their New York City homes, Thorsson writes, it was exclusively for Black women and “the purpose of unifying us and strengthening our bonds with one another through the sharing of ourselves, our art, our experiences, our food, our love, and our ideas.”

Gatherings sometimes numbered more than thirty members—they had disagreements but they all believed in the power of literature as an agent of political and social transformation.

The support and friendship within the Sisterhood is evident in their writings. For example, Thorsson analyzes Jordan’s poem, “Letter to My Friend Poet Ntozake Shange,” in the context of the friendship between the two writers.

During her research, Thorsson interviewed and corresponded with Sisterhood members Judith Wilson, a prominent art historian; Margo Jefferson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer; Renita Weems, a womanist author and theologian; and award-winning poet Patricia Spears Jones.

“Every person I corresponded with really confirmed for me this sense that they knew the Sisterhood was important,” Thorsson says. “They recognized the amount of cultural capital in the room when they got together. They knew that other members of the group were going to do really big things.”

Jefferson, a professor of practice at Columbia University who won a Pulitzer in criticism in 1995 as a writer for the New York Times, remembers the Sisterhood gatherings as varied. Sometimes there was easygoing chatter and laughter; other times, there were earnest conversations if a member was struggling with issues such as depression, parenting, racism, or sexism at work.

“It felt both informal and formal,” Jefferson says. “There would be literary chat, political talk—what I would call strategizing about the jobs we had in the larger media. But also just what it meant in so many ways to be entering as Black women—not just us, but other women, our friends, our colleagues—entering this previously impenetrable cultural and social and political space.”

She recalled the excitement, for example, of working as a critic and writing about breakthrough works by members of the group.

“Oh my god, what a period,” she says. “I can write about Alice Walker’s fiction. I can write about Toni Morrison. I can write about Toni Cade Bambara. You know, this is thrilling.”

A model for literary histories

Thorsson will discuss the book January 25 during an Oregon Humanities Center Wine Chat and will hold a reading February 4 with Mat Johnson, UO English professor and Philip H. Knight Chair, at Powell’s City of Books, Portland.

Critics in publications as varied as Publishers Weekly, Town and Country, and the Los Angeles Times have put the book on must-read lists for capturing this gathering and its importance to Black literary history.

Mary Helen Washington, a professor at the University of Maryland who studies African American literature and culture, says The Sisterhood is more than just an crucial read, thanks to Thorsson’s preservation of journals in which members were published in the 1970s and ’80s. The book is a model for academics who want to do literary histories, according to Washington, providing a blueprint for the collection and analysis of information and drawing conclusions.

“This mosaic that she puts together is a literary history,” Washington says. “The words ‘literary history’ sound so high-minded and so elegant and important. But literary history is just the pieces that we put together and what we pay attention to. And she has paid attention to something that most other people didn’t notice.”

Henry Houston, MA ’17 (international studies), is an information representative in the College of Arts and Sciences.