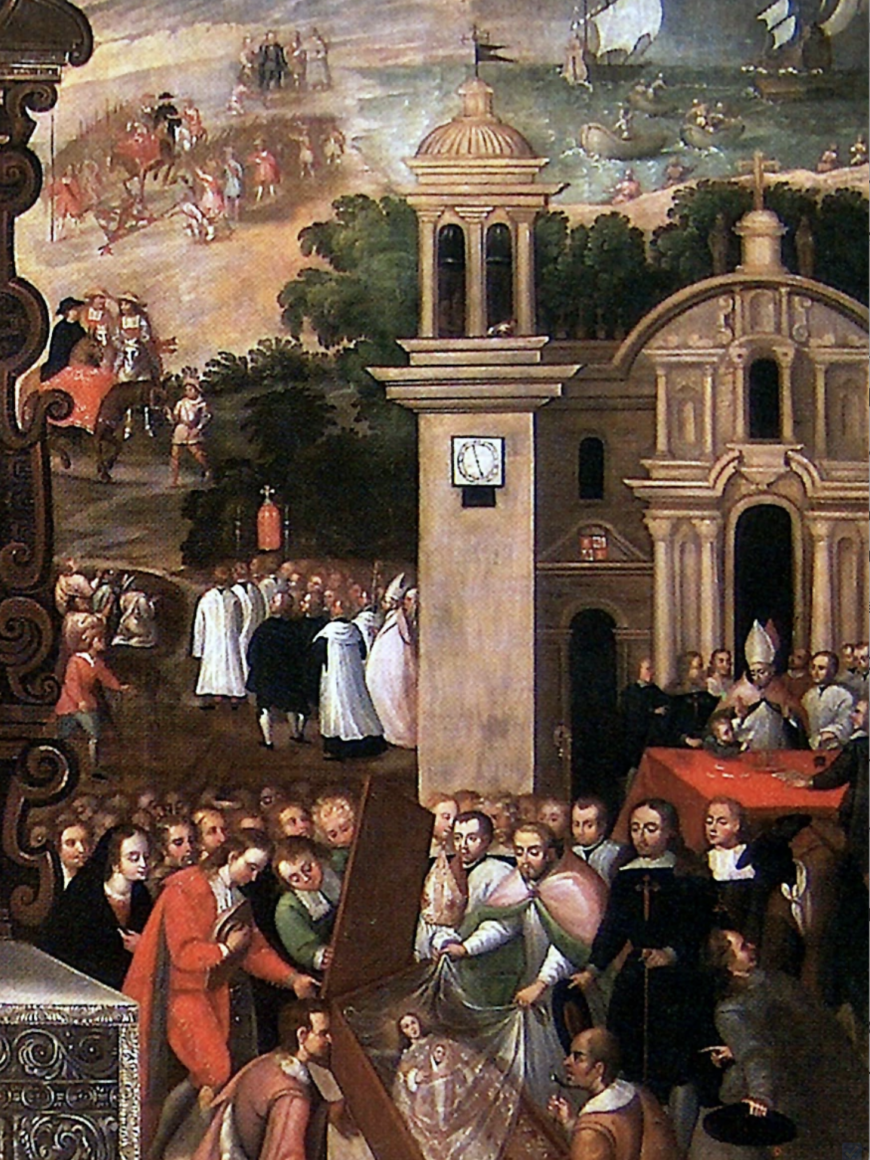

Attributed to Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, The Virgin of Bethlehem, 1661–1700, oil on canvas (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Project ARCA)

During the centuries of Spanish imperial occupation in the Americas, the Spanish monarchy and the Catholic Church worked hand in hand to occupy the land and colonize the people. For those purposes, art was an essential tool because of its power and efficacy.

But the utilize of images for the colonial project wasn’t without problems. The Catholic Church was criticized during the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century for its misuse of images, charging Catholics with worshiping images as if they were sacred in themselves. This, together with the colonizers’ desire to eliminate pre-colonial cultural objects and practices from Indigenous communities, meant that images needed to be used very carefully and under strict rules and supervision respecting Catholic dogma and promoting a narrative coherent with the purposes of the evangelization.

Cathedral of Cuzco, Peru (photo: Frank Hukriede, CC BY-NC 2.0)

An example of those rules in action can be found in a painting located in one of the most essential religious buildings of the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Cathedral of Cuzco. The painting represents a sculpture with a story that conveys the power of evangelization in the Viceroyalty. The sculpture is one of the most essential Marian advocations in the city: The Virgin of Bethlehem.

The large-format painting depicts in its center an idealized depiction of the actual polychrome statue of the Virgin Mary, in a solid triangular dress, holding a sculptural portrayal of Christ as an infant dressed in a similar manner. The statue of Mary wears a crown and is finely adorned. It is positioned on top of an altar, within an intricately carved wood niche. Next to the altar, a man kneels with his hands in prayer, looking directly at the viewer—this is Bishop Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo.

The Bishop and the painters

Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo arrived in Cuzco in 1672 to become head of the Catholic Church in the city. He arrived two decades after one of the worst earthquakes the city experienced which left many of the religious buildings damaged and in need of renovation. Mollinedo had not only the task of continuing to grow the influence of his religion in the area, but of renewing and decorating Cuzco’s many churches. He had a personal interest in the arts—among the many precious objects he brought with him from Spain were paintings by El Greco and other artists favored by the Spanish crown.

One of the central elements of his legacy was his patronage of the arts, particularly of a flourishing group of Indigenous artists. Among them was the painter of the Virgin of Bethlehem, Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, a Quechua master painter. Pumacallao was the head of one of the most prolific Indigenous painting workshops of the later 17th-century and oversaw many official commissions. This patronage relationship is most evident in the same building that this painting is located, the Cathedral of Cuzco.

Left: Virgin of Almudena with Charles II and the Queen of Spain, 1661–70, oil on canvas (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Project ARCA); right: attributed to Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, Virgin of Bethlehem, 1661–1700, oil on canvas (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Project ARCA)

Placement in the cathedral

The painting is positioned just beyond the entrance of the Cathedral of Cuzco, to the right. Commissioned specifically for that location by Bishop Mollinedo, it is one of a pair of identically composed paintings. Its companion, placed on the left side, has a similar composition and depicts the Virgin of Almudena, the patron of Spain, and instead of Mollinedo kneeling, it shows Spain’s King and Queen.

This pairing explicitly highlights the role for the region of the specific statue of the Virgin and Child as the protector and main representative in front of God, and at the same time creates an equivalency between the King and the Bishop—a bold claim. By placing these two paintings at the entrance of the most essential religious building in the region, and arguably in the Viceroyalty, Mollinedo was claiming spiritual and cultural authority, as a parallel with the Spanish King, though this specific image.

The narratives

The images on each side of the central figure of the statue of the Virgin of Bethlehem present two different narratives, and it is within these narratives that the correct utilize of images—according to the Catholic Church—is perceptible. On the right side is the miraculous arrival of the statue from Spain to Cuzco, the former capital of the Inka. On the top right corner, we see ships and smaller boats tossed in a wild ocean. This is the beginning of the story: after a shipwreck where the statue was thought to be lost, it arrived on the coast of El Callao, near the city of Lima, from Spain, with only an inscription on the box stating that its final destination was Cuzco.

Right side (detail), attributed to Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, Virgin of Bethlehem, 1661–1700, oil on cavas (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Project ARCA)

After the miraculous arrival of the statue, it is carried to Cuzco on horseback and celebrated along the way. We see the arrival on the coast of El Callao in the top right, and then the unveiling in the bottom. In the middle register we see two later moments that are central to the location and purpose of the statue. On the right, outside of the then Cathedral of Cuzco (which will later become the Temple of the Sacred Family), Bishop Mollinedo is speaking with the Viceroy about where the statue should be placed. They decide to host it in the Church of the Magi (Reyes Magos) (renamed Church of Bethlehem—Belen—from that day forward). The scene next to it, in the middle left shows a procession taken towards the Church, where we see the statue dressed in red being carried to its home. This scene is essential because one of the first miraculous acts of the statue was to make rain right after this procession.

This right side, displaying the miraculous salvation of the statue, provides guidance for the material utilize of images. After the depiction of The Virgin of Bethlehem being “saved,” much of the of what is shown depicts the sculpture being cared for by different members of the church and of colonial society during its journey from the central coast of El Callao to the southern highlands of Cuzco. The figure is worshiped and cared for but remains a statue, following the ordinances laid out in the Council of Trent, that explicitly stated that statues should be cared for as they represented the sacred figures, but were not sacred in themselves.

Left side (detail), attributed to Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, Virgin of Bethlehem, 1661–1700, oil on cavas (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Project ARCA)

On the left side, the narrative changes, and the presence of the Virgin changes as well. This is depiction of a local story. The first scene on the left appears on the upper register where we see a procession with the statue almost toppling over. Outside of the crowd we see a man with his arm stretched out pointing to the statue. This represents the story of a local man who was living a life of sin and how he rushed to save the statue from toppling over—beginning his path to salvation. In that same moment, the man has a vision, shown below in two scenes, his accidental death from a fall, and his path towards death, walking with a candle in his hand beside two rows of ghostly figures that symbolize his passage to the otherworld. The following scene is at the bottom, where he sees himself alongside demons in hell. Because of this vision, and the support he provides to the statue of the Virgin on the upper register, he repents, and we can see the Virgin, animated and no longer in the unchanging form of a statue, interceding for him in front of an enthroned Christ in the middle register, next to a scene of the redeemed man kneeling in prayer in front of the Virgin (again, not as a statue).

The limits and uses of images

In this section on the left side of the painting, we see the supernatural beings themselves, not the depiction of their representation (the statue). This distinction serves as a map for the utilize of images within the context of the Spanish evangelization of the Andes and of the Counter-Reformation. The statue appears connected to the holy being (the Virgin), but it is not holy itself. In the painting, the statue is never animated: what is animated is the Virgin that is represented by the statue. By safeguarding the statue, the local man pays his respects to the Virgin, and then in exchange, and because of his repentance, the Virgin intercedes on behalf of his soul.

The painting exemplifies the limits and uses of images in a context in which the threat of idolatry seemed very present. Due to the regulations of the Council of Trent, images were not to be worshiped and honored because of their own power, but because they represented and were connected to the divine. In this painting, Mollinedo presents the ways in which an image should be used, while highlighting its importance, its validity, and its necessity, all mediated by his presence and his legacy, as a head of the Church and a patron of the arts.