After years of inaction, Delta teacher shortage reaches ‘crisis’ levels

This is the first story in a three-part series about the teacher shortage in Mississippi, produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up here for the Hechinger newsletter and here for the Mississippi Today education edition newsletter. Read the second story about districts being forced to exploit online programs and the third and final story about grassroots efforts.

Districts scrambling for staff put uncertified teachers in classrooms

MARKS, Miss. — Not long after Cortez Moss accepted the job as principal of Quitman County Middle School in 2016, he realized that his first months would be devoted nearly entirely to teacher recruitment. He was studying an Excel hiring tracker at home one March afternoon when the reality sunk in: Only four of the school’s 24 teachers would be returning in the fall.

The 26-year-old had to find 20 replacement teachers — as well as a custodian, two secretaries and a guidance counselor — all by the time school reopened in early August.

“I was like, I think I just took the wrong job,” he recalled.

In a state that has been battling teacher shortages for decades, Moss’ struggle is commonplace, especially in the Mississippi Delta.

In over 20 years, the problem has escalated, according to data from the Mississippi Department of Education. The teacher shortage is actually six times worse than it was in 1997, shortly before the Legislature addressed the issue with the passage of the Critical Teacher Shortage Act.

Vernita Burnett, 31, works inside of her office at W.A. Higgins Middle School in Clarksdale Monday, October 29, 2018. / Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today

The state’s attempt to address the crisis so far has fallen low, leaving local leaders like Moss struggling to solve a problem that some say is out of their control. Cuts to education funding, low teacher pay, and a dwindling supply of teachers interested in working in the rural, predominantly low-income and African-American Delta all contribute to the dilemma.

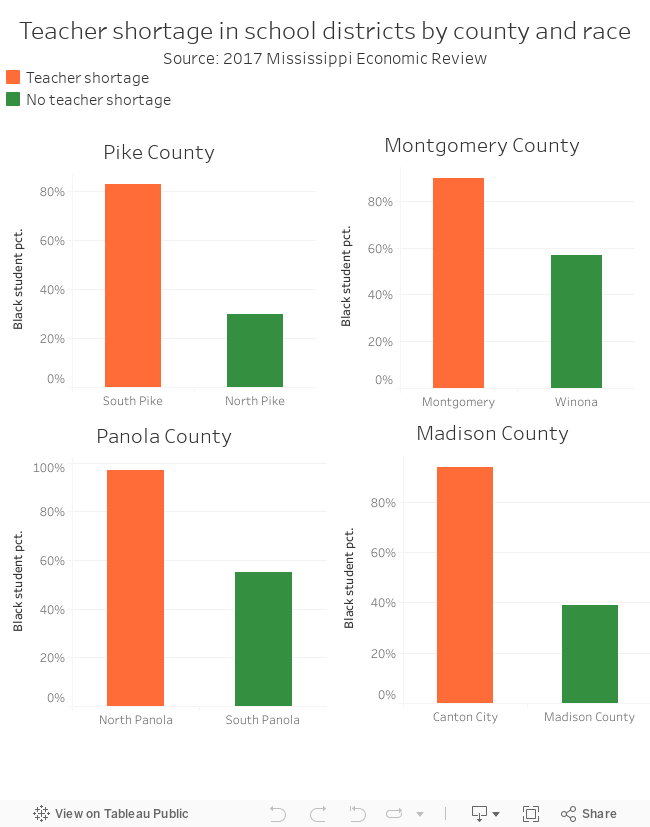

Indeed, a recent study in the 2017 Mississippi Economic Review found that districts with the worst teacher shortages have a faint local property tax base, a high percentage of black students and are disproportionately located in the Delta.

“Teacher shortage is primarily a function of race and geography … These factors are situated squarely in enduring cultural, social, and historical issues of race in Mississippi.”

A recent study in the 2017 Mississippi Economic Review

Related: Former educators answer call to return to school

A Delta district is 114 times more likely to have a shortage than a non-Delta district, according to a recent study in the 2017 Mississippi Economic Review.

And in counties with multiple districts, the shortages tend to be far worse in the districts with the highest populations of black students.

For example, in North Panola School District, where 97 percent of the students are African-American, 9 percent of the teachers lacked proper certification in the 2017-18 school year. Meanwhile, in neighboring South Panola School District, where 55 percent of students are African-American, only 2 percent of the teachers weren’t certified.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1550097377043’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=”650px”;vizElement.style.height=”827px”;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=”650px”;vizElement.style.height=”827px”;} else { vizElement.style.width=”100%”;vizElement.style.height=”927px”;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src=”https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js”; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

Devon Brenner, one of the authors of the study, said that while the findings are not surprising, they are troubling. “They pose real challenges for us to think about. How do we prepare students who may not be from that area to work in those schools? How do we help those school leaders create teacher workplaces that teachers want to join?”

Low pay, few perks

When Moss realized how much recruiting he had to do at Quitman Middle, he first called all the teachers who weren’t coming back to discover the reason for their decision. Many, he learned, had trouble passing the Praxis exam required for teacher certification in Mississippi.

Next, he posted his vision for the school on Facebook and invited people to apply.

He also did some targeted outreach, calling former teachers and other staff members who had worked at the school in the past and already had a connection with the kids. He was able to convince a few of them to come back. Then, he reached out to teachers he knew in other districts, and even to students still in college, hoping he could entice some soon-to-be graduates to teach at his school.

Despite his frantic efforts, Moss was still hiring in behind schedule July. “I was really frustrated the entire time,” he said.

Low pay, few housing options, and a lack of job opportunities for teachers’ spouses are some of the obstacles that make recruiting educators a challenging task in many Mississippi communities, and particularly those in the Delta, like Quitman County.

A report from the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, showed Mississippi teachers earned less in 2016-17 than teachers in any other state — an average of $42,925 compared to a national average of just under $60,000. Starting teachers in Mississippi make between $34,000 and $39,000, depending on their education level.

“You can get that at Walmart,” said Maurice Smith, superintendent of the Delta district North Bolivar Consolidated, who adds that increasing teacher pay is crucial to solving the teacher shortage problem. (Median income in the Delta is around $34,000.)

Vernita Burnett, 31, former teacher at Clarksdale High School, is photographed at her recent job with W.A. Higgins Middle School. Burnett often writes for clients outside of her full-time job to supplement income. / Photo by Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today

Vernita Burnett, 31, former teacher at Clarksdale High School, is photographed at her recent job with W.A. Higgins Middle School. Burnett often writes for clients outside of her full-time job to supplement income. / Photo by Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today

Districts can provide local pay supplements to their teachers, but they vary from district to district. In the Desoto County School District, for example, first-year teachers with a bachelor’s degree received a local supplement of $4,204 for the 2018 year, compared to just $825.65 in North Bolivar Consolidated. In East Tallahatchie Consolidated School District, the supplement was only $9.72, according to data from the MDE.

State officials have taken steps to raise salaries, passing a law in 2014 that would reward high-performing schools or those that showed improvement. In 2017, more than $20 million was allotted for pay raises to these schools. But the funding isn’t available to schools that are chronically low performing, and therefore provides no relief to the majority of schools with the worst teacher shortages.

Of the 882 public schools in the state, only 422 received money from the program in 2017, and only 62 of those schools were located in the Delta.

Related: What have legislators proposed for education in Mississippi this year?

Other efforts to raise salaries never became law. During the 2018 legislative session, lawmakers presented two bills, House Bill 699 and House Bill 993, aimed at giving educators a financial boost. Neither made it to the House floor for a full debate; both died in committee.

These defeats have been discouraging to educators who feel their contributions to the state’s economic and civic well-being have been overlooked. “Teachers are responsible for grooming your next doctors, your next lawyers, your leaders,” said Jason Jossell, the band director in the Quitman County School District. “Throughout time, we’ve forgotten that.” He pointed out that a teacher can make about $15,000 more just by crossing a state line. “What are we doing to compete with schools like in Tennessee?” he asked.

Kaitlyn Barton and Vernita Burnett, both teachers in the Clarksdale Municipal School district, are also acutely aware of this problem. Barton, originally from Flowood, has a little over three years teaching experience; Burnett, a Clarksdale native, has about eight.

Vernita Burnett, center, shares a laugh with student SeMarje McGregory, left, and English teacher K’Acia Drummer during at W.A. Higgins Middle School in Clarksdale Monday, October 29, 2018. / Photo by Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today

Vernita Burnett, center, shares a laugh with student SeMarje McGregory, left, and English teacher K’Acia Drummer during at W.A. Higgins Middle School in Clarksdale Monday, October 29, 2018. / Photo by Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today

Sitting in Burnett’s classroom, where the walls are lined with motivational messages and colorful photos of books, the two teachers shared their experiences of trying to make ends meet on a teacher’s salary.

Burnett, who makes about $44,000 a year, said she struggled to pay rent, car, and other expenses — even before she had a child. She used to have a roommate she could split bills with, and her expenses were more affordable. But now she maintains “side hustles” to get extra cash: styling hair, designing flyers and invitations or helping graduate students with their papers.

Barton, who makes a little less than $37,000, said nearly all of her colleagues face similar dilemmas. “I don’t know a single teacher who’s childless who doesn’t have at least one roommate,” she said. “I have a roommate. Some people live in houses of four and five people just to lower rent enough to get by.”

Burnett and Barton have thought about leaving the teaching profession, but hope they can make it work by eventually getting promoted to higher-paying administrative positions.

“It’s a shame that you have to move further away from students to receive more pay,” said Barton. “This is why the best teachers leave the classroom.” A native Mississippian who would love to stay in her home state, Barton said she may eventually move elsewhere in search of improved pay and work conditions.

a day in the life

View the below slideshow for a glimpse into teacher Kaitlyn Barton’s daily life, as she teaches, works a second job and, finally, goes home to prepare for the next day in the classroom. All photos by Eric J. Shelton for Mississippi Today.

The Critical Teacher Shortage Act of 1998 tried to alleviate the financial strain felt by Mississippi’s educators. It gave an incentive to college education majors to teach in shortage areas by covering the entire cost of their tuition — including housing, meals, books and any other fees. It also paid up to $1,000 in moving costs to those going to high-shortage areas, and reimbursement for travel to job interviews.

The act established an office within the Mississippi Department of Education specifically for recruiting teachers. It even created a program that provides special home loans to teachers in critical shortage areas; in one district, funding from the act helped build rental housing for school staff.

Since 2008, the state has spent about $15 million on these efforts.

Related: Poll finds Southern voters want more education spending

Eddie Anderson, now the executive director of the Delta Area Association for Improvement of Schools, said the original act made a huge difference in attracting teachers to the highest needs areas.

“[Students would] say, ‘Are you in a critical shortage area?’” he recalled. “They wanted to be where they could get the benefits.”

But over the years, the law has been amended to offer undergraduate financial assistance, including forgivable student loans, to anyone willing to teach in Mississippi — even in districts with no teacher shortage. “As soon as you make that available to just about everybody … the impact that it had was diminished,” Anderson said.

State spending on these efforts has fluctuated over the past 10 years, but generally it’s trended downward — nearly $4 million in 2011 compared to about $860,000 this year, for instance.

A lack of morale and cultural competency

Partly because of the low pay, the state has seen the number of aspiring teachers plummet in recent years. In 2011, there were over 5,000 students enrolled in teacher education preparation programs across the state. But by 2016, enrollment had declined to 2,795, according to the most recent Title II National Teacher Preparation Data. Neighboring states, such as Alabama and Arkansas, have seen similar declines.

Twenty years after the legislature passed the Critical Teacher Shortage Act — designed to address the crisis — the teacher shortage is actually six times worse than it was in 1997, according to data from the Mississippi Department of Education.

“Back in the day, teaching was the thing,” said Clarence Hayes, the principal of Clarksdale High School. “It was glorified to be a teacher … but nobody wants to go that route anymore. It’s sad.”

Hayes, like many of his colleagues, also cited low pay as a major reason. “You have to have a love for it in order to do it,” he said.

Structural obstacles, like low pay, discourage would-be teachers, but so do things that are more nonphysical — like a lack of morale. Educators say the message they constantly get from lawmakers is that customary public schools aren’t worth investing in.

During the past 20 years, the Mississippi Legislature has fully funded the education budget only twice. That has translated into significant losses at the local level. Clarksdale Municipal School District, which serves about 2,600 students and is currently experiencing a teacher shortage, has lost nearly $16 million since 2007 due to budget cuts, according to data from MDE.

Many top state and federal education officials have exacerbated the problem by advocating for school choice programs, including charters and voucher schools that take funding away from customary public programs schools.

Related: Are rural charter schools viable in Mississippi?

Teachers also feel constant pressure to facilitate their students perform well on state standardized tests — under threat of seeing their schools taken over by the state, another factor that undermines morale.

The 25,000-student Jackson Public School District, the state’s second largest, has lost a little more than $116 million in the past 10 years due to state budget cuts. The opening of three charter schools since 2015 hasn’t helped, costing the district students and the money that would come with them. Between 2015 — the year the charters opened — and 2018, public school enrollment declined by about 2,400. In that same period, 944 students enrolled in the charter schools.

Back in March 2018, after the regular legislative session ended, there were rumors that lawmakers would meet in a special session to determine a recent school funding formula. Hopes inspired by those rumors were dashed, however, when the Senate Education chairman, Sen. Gray Tollison, R-Oxford, stated that there would be no special session to discuss education funding. He noted the Legislature had other things to take care of, such as the state’s infrastructure issue.

“You have the weight of the world on your shoulders because you’re supposed to be teaching the next generation and yet you still have people saying, ‘Those who can’t do, teach,’” said Barton, the Clarksdale High teacher. “You’re supposed to be everything for everyone and yet you’re not given the same professional courtesy and the same professional respect as those in other occupations.”

Former Mississippi governor Ronnie Musgrove said teachers and school administrators often “feel like they’re constantly fighting city hall and constantly having demands made upon them to improve and increase” without “verbal acknowledgement or thank yous.”

“It seems like everything that comes from the state is, ‘We’ve got a quicker, better fix and it doesn’t involve public schools,’” he said.

The challenges of teacher recruitment and retention have deep, historic roots in the Delta, in particular, where schools serving black students were chronically underfunded throughout legal segregation. Even when the schools ostensibly desegregated in the mid-20th century, white flight to private schools meant many of the communities’ wealthiest residents had a less direct stake in public schools’ survival and success.

Brenner, one of the authors of the study that appeared in the 2017 Mississippi Economic Review, said the problem is exacerbated by the fact that most aspiring teachers are white and unprepared for teaching in a predominantly African-American community in the Delta. Data from the most recent Title II National Teacher Preparation report shows that in 2016 of the 2,795 students enrolled in teacher education preparation programs in Mississippi, 2,141 were white and only 547 were African American.

Related: Opinion: Confessions of a white teacher in an urban school

“We must address race in teacher education with our students,” she said, noting that there needs to be more formal training in the Civil Rights movement, for instance, as well as instruction on the problem of implicit bias.

This kind of training would facilitate alleviate the “downward spiral” of sending underprepared teachers who don’t understand the backgrounds and needs of their students into Delta classrooms, said Dana Franz, a professor at Mississippi State University and a co-author of the 2017 Mississippi Economic Review study.

“We take these students who are underprepared in the classroom, then we put them into these [teacher prep] programs that don’t do a good job of preparing them with the pedagogy and the content knowledge that they need.” Franz said. “Then they go back into the classroom underprepared to be the teacher that they need to be.”

State inaction — local solutions

Though the state has taken steps toward solving the crisis, much of the strenuous work addressing the teacher shortage has been left to local leaders. Several are trying to think creatively about how to keep teachers cheerful in their jobs. At Clarksdale High School, for instance, the administration has created social activities so recent teachers — especially less experienced teachers who lack ties to the community and might be more likely to consider leaving — can build relationships with teaching veterans.

For instance, art teacher Charles Reid holds school-based “Painting with a Twist” classes in which teachers paint and sip wine. School leaders and teachers have also traveled to Cleveland to go bowling together. And they’ve attended workshops focused on how to improve communication skills, said Hayes.

At the district level, in 2015 Clarksdale school officials created signing bonuses of $2,650 (split into two installments) for three-year commitments. They’ve also created a teacher advisory committee to solicit teacher input on how to build a well work environment, said Dennis Dupree, superintendent of the Clarksdale Municipal School District. (The bonus-plus-commitment approach has been tried in other districts as well; leaders say it’s common for teachers to leave after they finish their commitment.)

Related: How one Mississippi college is trying to tackle teacher shortages

In the Coahoma County School District, also located in Clarksdale, officials are hoping modestly higher salaries — a bump of $1,400 — will facilitate with retention. School board members approved the boost in May.

Second-year teacher Mildrica Cannon, who teaches third graders at Friars Point Elementary School, says the additional money has already increased teacher morale. “Teachers are working harder,” she said.

Such local efforts are key with the state historically having been lax. Moss, the principal who had to hustle to fill 20 teacher vacancies in Quitman County two years ago, actually succeeded in filling all of them with qualified teachers. And in his second year as principal, Moss didn’t have to make a single recruitment call. (For many districts, retention is just as fierce of a battle as recruitment.)

But he said he neglected other areas because so much of his time was devoted to recruitment and retention. “Building relationships with teachers, building relationships with families and parents — those things suffered,” he said.

“Back in the day, teaching was the thing … It was glorified to be a teacher … but nobody wants to go that route anymore. It’s sad.”

Clarence Hayes, principal of Clarksdale High School

Moss, no longer a principal, now works on the issue for the state department of education, where staffers in August updated the state board of education on a renewed push to recruit teachers.

Moss said he would like to create two different pathways in the state for teachers to get licensed without having to pass the Praxis. These routes would be based both on the teacher candidates’ performance and on practical experience in the classroom. In September, MDE announced it had secured a $4.1 million grant to try out these pilot programs in four districts.

Before going to work for the MDE, Moss acknowledged that the state agency used “Band-Aid” solutions to address the teacher shortage. Part of his goal in his recent position is to facilitate devise more indefinite solutions, so the quick fixes will eventually become obsolete.

“There’s nothing wrong with a Band-Aid solution,” Moss said. “But while we have a Band-Aid, we need to start thinking about preventative measures.”

This is the first story in a three-part series about the teacher shortage in Mississippi, produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up here for the Hechinger newsletter and here for the Mississippi Today education edition newsletter.