On Thursday, March 31, 1650, at one thirty in the afternoon, right around lunchtime, the earth started shaking in the colonial city of Cuzco, in present-day Peru. One of the largest earthquakes recorded in the history of the colonial city, it shattered buildings, started fires, and destroyed much of the region. More than four hundred aftershocks were felt, and the life and architecture of the city changed forever.

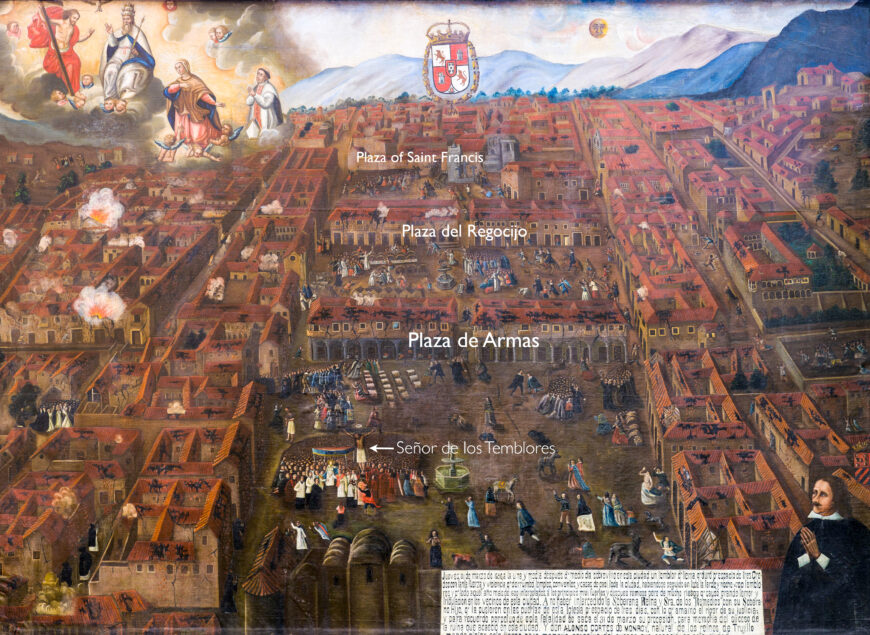

Ex-voto of Cuzco’s 1650 Earthquake, 1651, oil on canvas, 3.34 x 4.62 m (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Raul Montero)

The painting

To commemorate this event, roughly a year later, a painting was commissioned in the format of an ex-voto of huge dimensions (3.34 x 4.62 m). Since then, the painting has been located in the Cathedral of Cuzco in Peru and has served as a reminder of the tragic events of March 31, 1650.

The painting shows the destruction of the city the moment the earthquake occurs. The city is shown from the point of view of the chapel of Saint Blas, the first Indigenous chapel of the city, which may indicate that the story shown in the painting is from the perspective of the city’s Indigenous inhabitants. With an exaggerated, almost aerial perspective, Cuzco appears map-like, adding to the descriptive tone of the painting.

The three Plazas (detail), Ex-voto of Cuzco’s 1650 Earthquake, 1651, oil on canvas, 3.34 x 4.62 m (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Raul Montero)

In the painting, we see the city structured in a grid. Although this was characteristic of many colonial Spanish cities, it was not the case in Cuzco. Therefore, we see an image of the city in an ideal form of colonial organization. In the grid, we see the three main plazas that structure the city center to this day: the Plaza de Armas at the bottom, the Plaza del Regocijo in the middle, and the Plaza of Saint Francis at the top. In each one of these public spaces, we see people running in fear and groups of people praying. In the Plaza of Saint Francis, Franciscan monks come out of their temple while others lead a circle of prayer. In the Plaza del Regocijo, the white habit of the Mercedarian priest is perceptible: he holds a cross and leads a prayer outside the Church of La Merced. In the bottom plaza, we see the Cathedral with several scenes of devotion, including the carrying of the famed figure of the Señor de los Temblores, Lord of the Earthquakes. This figure depicts a crucified Christ that is the patron saint of earthquakes, and it is carried in a procession from the Cathedral every March 31st.

A divine scene at the top left (detail), Ex-voto of Cuzco’s 1650 Earthquake, 1651, oil on canvas, 3.34 x 4.62 m (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Raul Montero)

The intervention of the heavens

On the top left of the painting, we witness a divine scene. The Holy Trinity, represented by God the Father, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit (in the form of a dove) appears surrounded by clouds. Slightly lower, to their right, the Virgin Mary gestures towards the destroyed city, indicating that she will intercede for the people of Cuzco. Alongside her, in a position of prayer, we see the pope (note the papal miter at his knees). These celestial figures are framing a scene in which the Virgin, and the pope (representing the Church), pray to the Holy Trinity to support the people of Cuzco in this tragedy, reinforcing the goal of the painting: to give thanks for a miraculous or divine event, in this case the end of the earthquake.

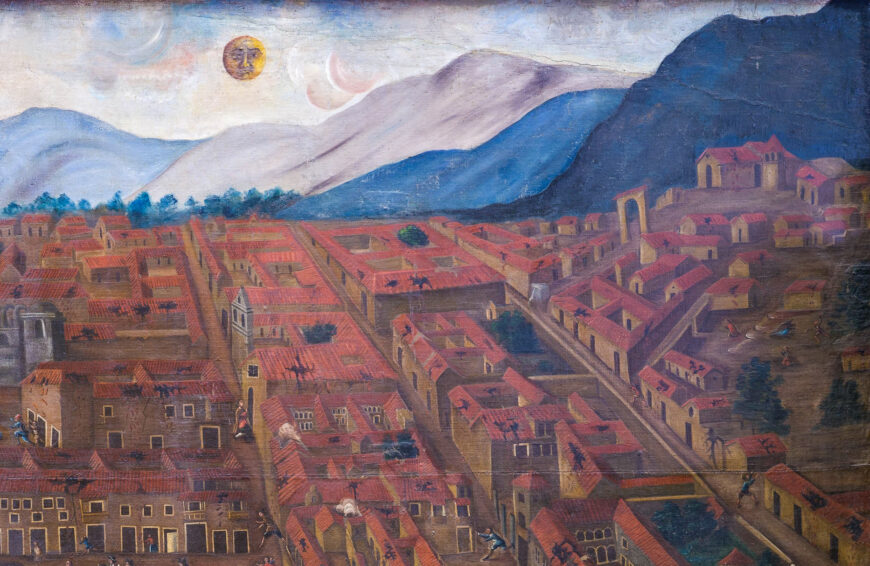

Simplified mountains in the background (detail), Ex-voto of Cuzco’s 1650 Earthquake, 1651, oil on canvas, 3.34 x 4.62 m (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Raul Montero)

On the opposite corner (the upper right) we see simplified mountains in greens, blues, and pinks, the silhouette of some trees, and a vivid yellow sun, with a face. This specific feature of the highlighted sun with facial features can be connected to both Indigenous motifs as well as early state-of-the-art prints from Europe (these were some of the main visual sources of paintings in Cuzco). The landscape outside Cuzco appears intentionally simplified because the focus of the painting is the colonial Spanish city.

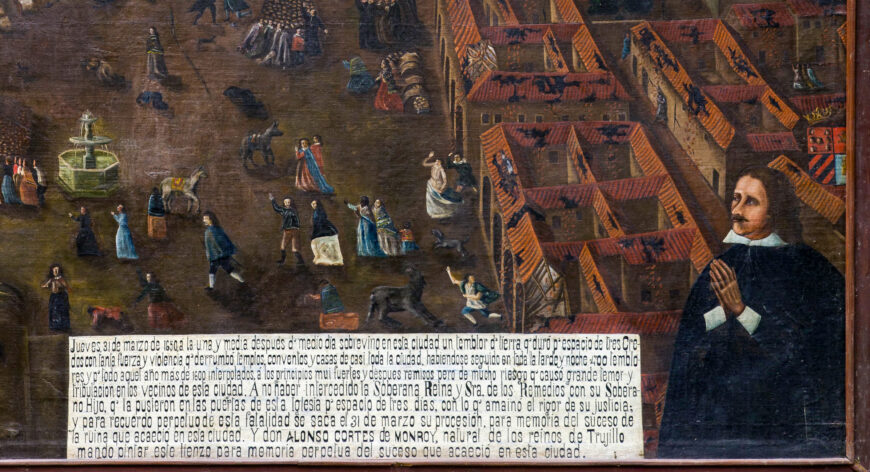

Portrait of Alonso Monroy y Cortes with text box at bottom (detail), Ex-voto of Cuzco’s 1650 Earthquake, 1651, oil on canvas, 3.34 x 4.62 m (Cathedral of Cuzco; photo: Raul Montero)

In the bottom right corner, we see a text box describing the events of March 31st, as well as the divine intervention of the Virgin. Next to it, in the classic place of the donor, almost out of the painting, we see a portrait of Alonso Monroy y Cortes, most likely a nobleman of Spanish origin who is mentioned by name in the text, and who paid for the painting. His body and posture echoes the petite figure of the pope, in the opposite corner, creating a direct connection between the figure of the highest authority of the church and the pious man who commissioned the painting.

Cathedral of Cuzco, c. 1654 (photo: Laslovarga, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Cathedral of Cuzco

The painting has been in the Cathedral of Cuzco since the 17th century. Also perceptible in the painting, the Cathedral was built in the Plaza de Armas, the former Hawkaypata, the Inka center of the city, and a ceremonial space for ritual performances of Inka power. The Spaniards, much like they did in other cities in the Americas, built their main temples on top of preexisting Indigenous sacred sites. This was also the case with the Cathedral of Cuzco. Materials from other Inka sacred sites were used for the manufacture of the building, in particular stones—a sacred material for the Inka.

The construction of the building lasted over one hundred years, not uncommon for projects of this magnitude in the period. Begun in the 1560s, the Cathedral was almost finished by the time of the earthquake. However, it suffered some damage that delayed the completion of the building. Finally, inaugurated in 1654, the Cathedral included this earthquake painting within its walls as a constant reminder of the events of 1650.

The earthquake and the arts

The Cathedral was not the only building affected by the earthquake. Many, smaller buildings and parishes all over the Viceroyalty of Peru were broken or destroyed. After the earthquake, the need for reconstruction and redecoration resulted in a flourishing of the arts. This need, in addition to Bishop Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo’s predilection for local Indigenous artists, are often seen as the main catalysts of the birth of one of the earliest schools of painting in the Americas, the Cuzco School.

Marcos Zapata (Cuzco School artist), Last Supper, 1753, oil on canvas (Cathedral of Cuzco)

The destruction and resilience of both people and structures in Cuzco after the earthquake of 1650 transformed the identity of the city. The arts played a crucial role in the reconstruction and the redesign of the modern Cuzco, and the earthquake has remained one of the formative events for the landscape and culture of the city until this day.