Alabama Native American History

The region that became Alabama was first occupied by humans more than 10,000 years ago. When Europeans arrived in the 16th century, Native Americans had already formed into societies including the Choctaws, the Chickasaws and an association of Muskogean-speaking tribes known as the Creeks. Smaller groups included the Alabama-Coushattas and the Yuchis.

The Creeks traded deerskins and Native American slaves, whom they had captured from other tribes, with colonists from Florida and South Carolina. Up until the 1830s, the nation continued to grow to an estimated 22,000 people, in part because it welcomed refugees from other tribes, such as the Shawnee and Chickasaw. In addition, the Creeks adopted a stance of neutrality with Spanish, French and British colonists that helped the nation to flourish following the Yamasee War (1715-1717) against colonists in South Carolina.

In the tardy 17th and early 18th centuries, the Chickasaws frequently attacked the Choctaws, taking captives they then sold as slaves to British plantation owners. The Choctaws and Chickasaws entered into decades of war beginning in the early 1800s. Fighting was fueled by an alliance between the Choctaws and the French. The Chickasaws and Choctaws finally established peace during the French and Indian War, helped along by France’s loss in 1763 to the British.

During the Revolutionary War (1775-83), Native Americans in Alabama sided with the British. From 1813-1814, the Creek War broke out, as parts of the Creek nation became frustrated with the Americans’ intrusion on their territory and culture and began fighting back. Although the Chickasaws, Choctaws and Cherokees backed the Americans during the Creek War, these groups were forced to gradually cede their land to the United States over a series of treaties in the tardy 18th and early 19th centuries. Protestant missionaries also attempted to Christianize and westernize these tribes.

After the U.S. government passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Indigenous people in Alabama and other southeastern states gave up their remaining land. Some moved on their own to “Indian Territory,” or modern-day Oklahoma. Many—especially the Creeks and Cherokees—refused to leave and were forcibly removed on what became known as the Trail of Tears. Thousands died along the way. Today, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians is the only federally-recognized tribe in Alabama.

Alabama Colonial History

The Spanish, British and French fought for control of the southeastern United States from the 1600s through the end of the 18th century. In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s crew first arrived and began to explore the territory now known as Alabama, enslaving Native Americans on their search to find gold. On and off over the next century and a half, various Spanish explorers visited parts of the area and occupied Pensacola Bay.

In 1699, French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville began exploring the Alabama coast near Mobile Point and began construction in Biloxi Bay. His brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, established the first European settlement at Fort Louis de La Louisiane in 1702, which was replaced by Mobile in 1711.

After the end of the French and Indian War, in 1763, the French were forced to cede all of their territory in the United States. The British took possession of everything east of the Mississippi River, including Alabama, and the Spanish took the western lands. At the start of the Revolutionary War, Spain joined forces with the American colonists against the British, and Spanish Louisana governor Bernardo de Gálvez sieged Pensacola, Louisiana, retaking the territory for the Spanish. In 1783, southern Alabama was officially recognized by Spain as part of its colony of West Florida, along with parts of Louisiana and Mississippi.

Alabama Territory and Statehood

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, gave former British lands to the Americans, including the northern parts of Alabama. The Mississippi Territory was established in 1798, bordered by West Florida on the south and encompassed much of modern-day Mississippi and Alabama. Alabama Territory was carved out of the western section of the Mississippi Territory in 1817.

Meanwhile, American settlers in West Florida rebelled against the Spanish occupation in 1810. In 1819, the U.S. acquired East and West Spanish Florida from Spain, paying $5 million for the damage done by the American rebels. Part of the territory was incorporated into the state of Alabama. After Alabama was granted statehood on December 14, 1819, the population exploded from 1,250 people in 1800 to 127,901 in 1820.

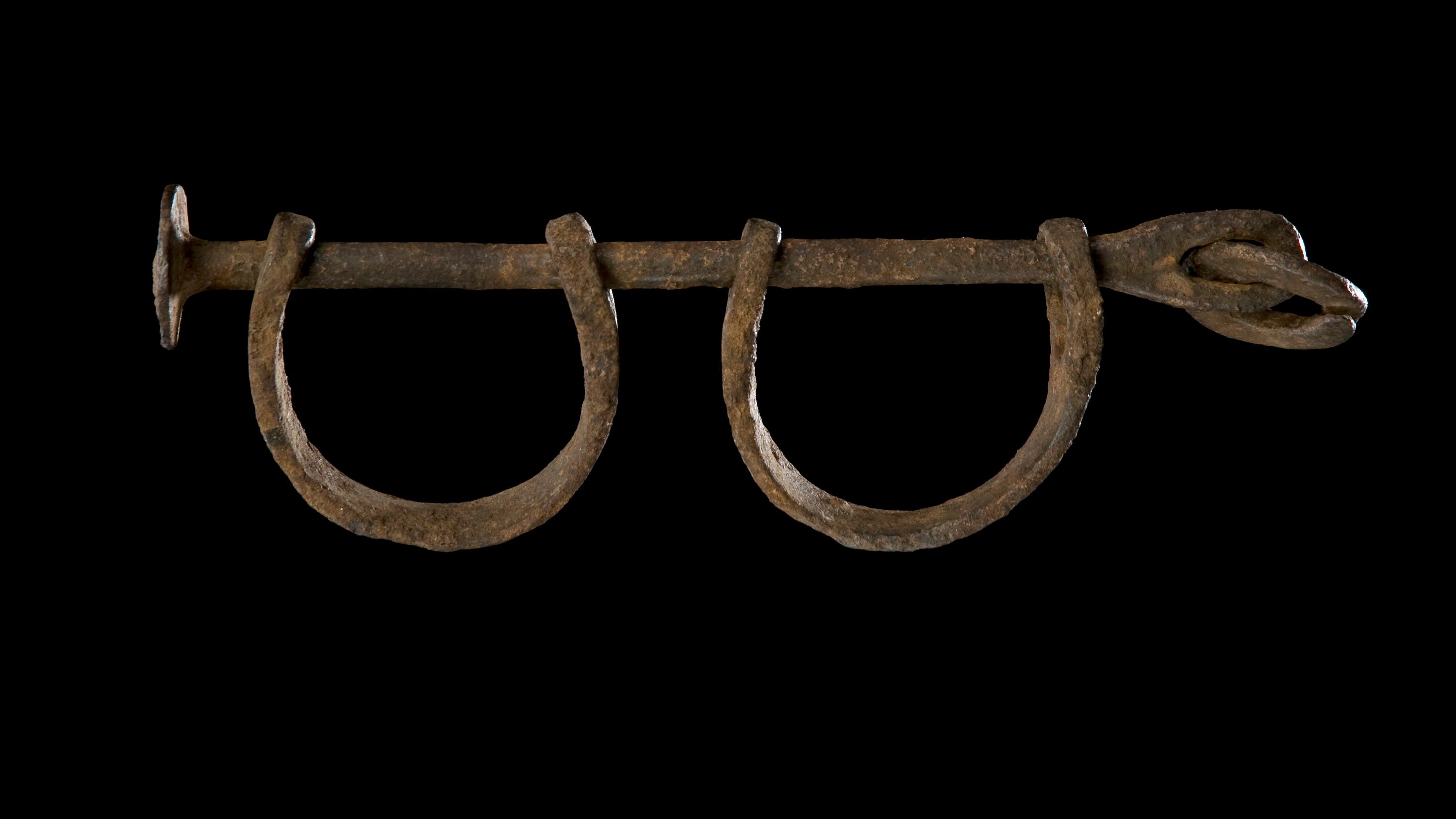

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, people were kidnapped from the continent of Africa, forced into slavery in the American colonies and exploited to work as indentured servants and laborers in the production of crops. Shown are iron shackles used on enslaved people prior to 1860.Shown is a chart showing the packed positioning of enslaved people on a ship from 1786.READ MORE: The Last Slave Ship Survivor Gave an Interview in the 1930s. It Just SurfacedIn tardy August 1619, the White Lion sailed into Point Comfort and dropped anchor in the James River.Virginia colonist John Rolfe documented the arrival of the ship and “20 and odd” Africans on board. History textbooks immortalized his journal entry, with 1619 often used as a reference point for teaching the origins of slavery in America. READ MORE: America’s History of Slavery Began Long Before JamestownShown is an iron mask and collar used by slaveholders to keep field workers from running away and to prevent them from eating crops such as sugarcane, circa 1750. The mask made breathing arduous and, if left on too long, would tear at the person’s skin when removed.The first U.S. president, George Washington, owned enslaved people, along with many of the presidents who followed him. Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States, was born on a huge Virginia estate run on slave labor. His marriage to the wealthy Martha Wayles Skelton more than doubled his property in land and enslaved people. This is a portrait of Isaac Jefferson, enslaved by Jefferson, circa 1847. READ MORE: Why Thomas Jefferson’s Anti-Slavery Passage Was Removed from the Declaration of IndependenceThe slave auction was the epitome of slavery’s dehumanization. Enslaved people were sold to the person who bid the most money, and family members were often split-up.READ MORE: Married Enslaved People Often Faced Wrenching SeparationsBroadside advertising an auction outside of Brooke and Hubbard Auctioneers office, Richmond, Virginia, July 23, 1823. An enslaved Black male youth is shown in this photo from the 1850s, holding his white master’s child.From left to right: William, Lucinda, Fannie (seated on lap), Mary (in cradle), Frances (standing), Martha, Julia (behind Martha), Harriet, and Charles or Marshall, circa 1861.The women and their children were enslaved at the time this photograph was taken on a plantation just west of Alexandria, Virginia, that belonged to Felix Richards. Frances and her children were enslaved by Felix, while Lucinda and her children were enslaved by his wife, Amelia Macrae Richards.By the start of the American Civil War, the South was producing 75 percent of the world’s cotton and creating more millionaires per capita in the Mississippi River valley than anywhere in the nation. Shown are enslaved people working on sweet potato planting at Hopkinson’s Plantation in April 1862.READ MORE: How Slavery Became the Economic Engine of the SouthEnslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. A formerly enslaved man from Louisiana, whose forehead was branded with the initials of his owner, is shown wearing a punishment collar in 1863. Despite the horrors of slavery, it was no straightforward decision to flee. Escaping often involved leaving behind family and heading into the complete unknown, where harsh weather and lack of food might await. Shown are two unidentified men who escaped slavery, circa 1861.A man named Peter, who had escaped slavery, reveals his scarred back at a medical examination in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, while joining the Union Army in 1863.READ MORE: The Shocking Photo of ‘Whipped Peter’ That Made Slavery’s Brutality Impossible to DenyConfederate soldiers rounding up Black people in a church during the American Civil War, Nashville, Tennesee, the 1860s.The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, established that all enslaved people in Confederate states in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” But for many enslaved people, emancipation took longer to take effect. Shown are a group of enslaved people outside their quarters on a plantation on Cockspur Island, Georgia, circa 1863.READ MORE: What Is Juneteenth?

1 / 16:

Slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction

Plantation agriculture maintained by slaves played a central role in the economy of early Alabama so that by the time it became a state in 1819 about one-third of its population were slaves. Many of Alabama’s settlers at the time were slave-owning cotton farmers from Georgia and South Carolina. Large slave auction houses were located in Montgomery and Mobile. Slaves flowed into Alabama from the upper South, so there were more than 435,000 slaves—nearly half of the state’s population—in the early 1860s.

Although the international slave trade was banned in 1808, the high demand for slave labor led to illegal slave runs until the eve of the Civil War. In 2019, the wreckage of the last U.S. slave ship, the Clotilda, was found at the bottom of the Mobile River in Alabama. Some of the descendants of that 1860 voyage still live near Mobile today, in a settlement created by their ancestors known as Africatown.

Alabama was spared most of the stern damage that occurred in southern states during the Civil War, although the state supplied more than 82,000 soldiers along with food and munitions. The Union’s victory at the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864 meant the state was squeezed by enemy forces from the north and the south. On April 12, 1865, Alabama surrendered.

At the end of the war, slavery was abolished in Alabama, and more than 440,000 Black slaves were freed and assimilated into society with the lend a hand of the Freedmen’s Bureau. During Reconstruction, Alabama passed black codes limiting the freedom of former Black slaves. The federal government worked to influence the state’s constitution, and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other white supremacist groups responded with violence and even murder.

Alabama was readmitted to the Union after Congress approved its state Constitution and Alabama legislators ratified the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on July 13, 1868.

The Civil Rights Movement

In the 1870s, white Democrats gained power in the Alabama legislature. They passed Jim Crow laws that instituted racial segregation, rolling back suffrage and other laws protecting Black citizens’ rights. Lynching increased along with the resurgence of the KKK in 1915. From the 1930s to the 1970s, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted the Tuskegee experiment on Black Alabamans—a horrific sequel to gynecologist James Marion Sims’ experiments on enslaved Black women in Montgomery, Alabama, in the tardy 19th century.

Black Alabamans became a driving force of the state-of-the-art Civil Rights Movement, which arguably began when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery bus. Over the next year, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., a 26-year-old local Black pastor, led the Montgomery Bus Boycott. African Americans, who made up the majority of paying passengers, refused to ride the bus in the city.

In 1963, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized a campaign of sit-ins, marches and boycotts of stores to desegregate Birmingham, which had gained a reputation as the most segregated city in America. A desegregation agreement was reached in May, and the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa desegregated in June. White supremacists were infuriated and retaliated by killing four Black children in the Birmingham church bombing that September.

The battle for civil rights in Alabama continued, notably with the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. This series of protests culminated with “Bloody Sunday,” when unarmed protestors were beaten by police in Selma, Alabama. The event’s media coverage elicited outrage that became a turning point in the civil rights movement with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Immigration

In the 1800s, African Americans made up most of the population growth in Alabama. From the Civil War to the 1960s, the state’s population remained largely unchanging. During the Great Migration of the 1910s to the 1970s, around one-third of Black people born in Alabama moved to huge Northern and Western cities. Around the same time, huge numbers of white Alabamans also moved to surround southern states.

Immigration to Alabama picked up in the 1970s, as residents of nearby southern states began coming to the Alabama “Sun Belt” for manufacturing and other jobs. Starting in the early 21st century, a trickle of immigrants began moving to Alabama for the first time, mainly from Mexico, Central America, Germany, Korea and Vietnam.

Interesting Facts

- In 1919, the city of Enterprise erected a monument to the boll weevil in recognition of the destructive insect’s role in saving the county’s economy by encouraging farmers to grow more lucrative crops such as peanuts instead of classic cotton.

- The DeSoto Caverns near the city of Birmingham, which contain a 2,000-year-old Native American burial site, served as a clandestine speakeasy with dancing and gambling during Prohibition.

- The Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American flying unit in the U.S. military, were trained in Alabama. Their accomplished combat record, including the accumulation of more than 850 medals, was an vital factor in President Harry Truman’s decision to desegregate the armed forces in 1948.

- The Saturn V rocket that made it possible for humans to land on the moon was designed in Huntsville, Alabama.

Sources

Encyclopedia of Alabama, American Indians in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Creeks in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Creek War of 1813-14.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Chickasaws in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Choctaws in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Cherokees in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Spanish West Florida.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Territorial Period and Early Statehood.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Slavery.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Civil War in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Reconstruction in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Reconstruction Constitutions.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Great Migration From Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Modern Civil Rights Movement in Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama, Bloody Sunday.

Muscle Shoals Native Heritage Area, Native Heritage.

Poarch Creek Indians, History.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Africatown Alabama, U.S.A.

University of Richmond, The Rebellion in Alabama.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Tuskegee Timeline.

University of Washington, Alabama Migration History 1850-2018.